War on Warhole

Resin, gold-painted shovel

Installation, 2009 (lost)

Installed at:

SLOT Project Space, Alexandria

Year: 2009

Themes: Post-Pop, Kitchen Table Production, Poetics of the Scatter, Scattergun Approach, Modularity & Portability, Labour and Process, Playful Irony, Tools as Metaphor

Digging for stars with a nonexistent map. Armed with a golden shovel, looking for something real. A war on fame, fought with spray paint and resin.

Are these tools of critique? Or symbols of complicity? Am I standing outside the system, throwing stones? Or am I down in the mud with the rest, digging?

I made this piece during a time I felt thrown - by the art world and the wider world - by the strange sense that everything I thought I knew about meaning-making had blown up and come undone. When Tony and Gina invited me to make a work for SLOT, I was midway through one of my failed attempt at re-training into something else. Anything other than being an artist. I’d just recovered enough from another round of severe depression to be functional, at least- to attend university.

I cast small stars from semi-translucent resin using IKEA ice moulds I had lying around at home, at the kitchen table, after meals. I could only make a small batch at a time. It was a slow process. I think I wanted to make a truckload, to fill the floor completely at SLOT- to have the shopfront glass act like an aquarium with the stars piled up, like a dark waterline. But it was winter, and I had the flu. So I gathered what I was able to make and once at SLOT, scattered them across the floor. Like fallen dreams, party remnants, or dead satellites. I bought a shovel from the hardware store and spray-painted it gold. I wasn’t sure why - to collect the stars? To bury them? A garish attempt to look slightly less arte povera? I wasn’t even sure if the shovel belonged in the piece. But there it was anyway.

Maybe it was a nod to gardening.

A nod to an imaginary parallel life where I tend vegetables and flowers, instead of chasing acceptance and validation.

The title War on Warhole was a typo. I meant to write Warhol, but “Warhole” slipped out instead - and it made me laugh. It rhymed with arthole - which, at the time, felt about right. A dumb joke that would’ve made my five-year-old self laugh - but also a small truth. I found the art world confusing, brilliant, ridiculous, and painful all at once. And yet I wasn’t exactly outside of it, even if I wasn’t in it either. In my disorientation, I kept the title.

Maybe I was digging into something - not just reacting to Pop Art’s shiny surfaces, but to the hollow pit I found myself beneath. The kind of emptiness that creeps in after years spent chasing meaning in a world I didn’t fully understand, and that mostly compounded my anxieties.

Tools and implements have their own art history. Duchamp’s snow shovel (In Advance of the Broken Arm) turned one into an absurd gesture - all form, no function. Joseph Beuys used tools as relics of healing and revolution. David Medalla once stuck knives on a wall - not to wound, but what I read as a kind of psychic self-defence through art. My shovel is spray-painted gold. It looks heavy with something, but it doesn’t do anything. It just dully sparkles, like a wallflower in a corner.

The stars, too, are overburdened symbols - fame, childhood, hope, the sky. But mine are semi-transparent plastic. Like frozen tears that don’t melt. Some are so black they are nearly opaque. I thought they reminded me of Félix González-Torres’ scattered candy piles on the floor, closer to discarded party favours than constellations.

Like other works I’ve made, I liked that this one was modular - that I could fill a whole room full of stars and then pack them into a shoebox. Somewhat practical, in my world of impracticality.

The title sounds grand, but I wasn’t trying to make a grand work.

I just wanted to make something that held how I felt:

fallen, fragile, contradictory holding up appearances, a worker carrying on.

This piece isn’t neat. It’s not an attack. It’s not triumphant.

It’s a quiet mess - made of a found object, resin, and a vague sense of misfired purpose.

If it says anything, maybe it’s this:

I’ve been digging for something real.

And it’s making me unhinged.

Winter blues - coughing in the cold

Photographs from the time machine with Tony Twigg and Gina Fairley, standing in the art-lined hallway of their home, directly behind SLOT’s shopfront.

Cleaning the windows and installing the work at Slot Projects Alexandria w/ Tony Twigg

The Sound and the Fury (Signifying Nothing)

also called: Untitled, 2007

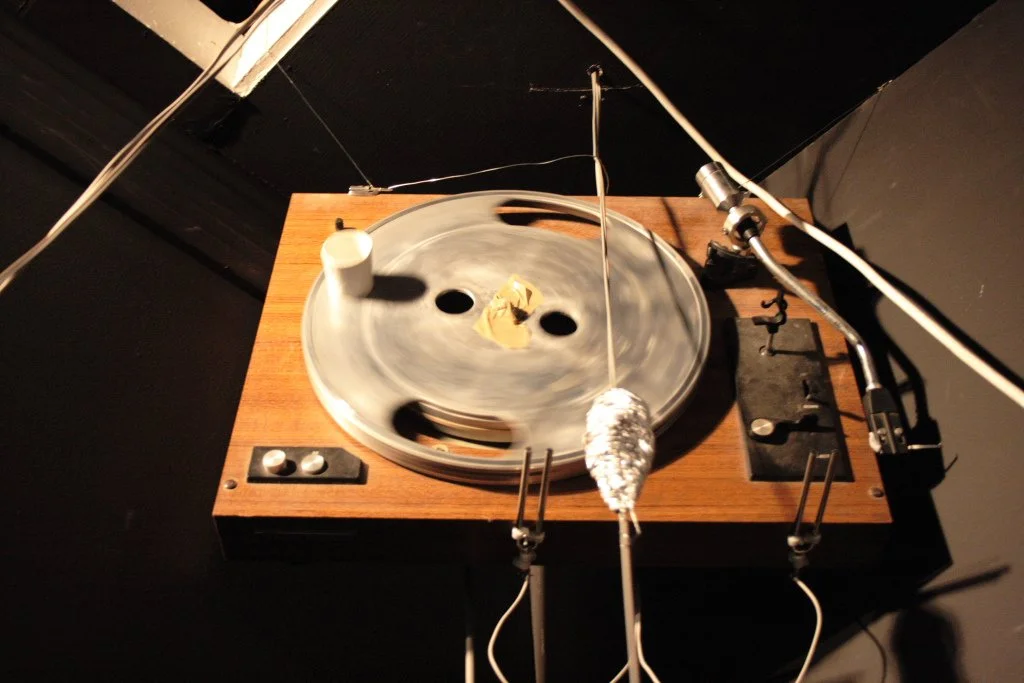

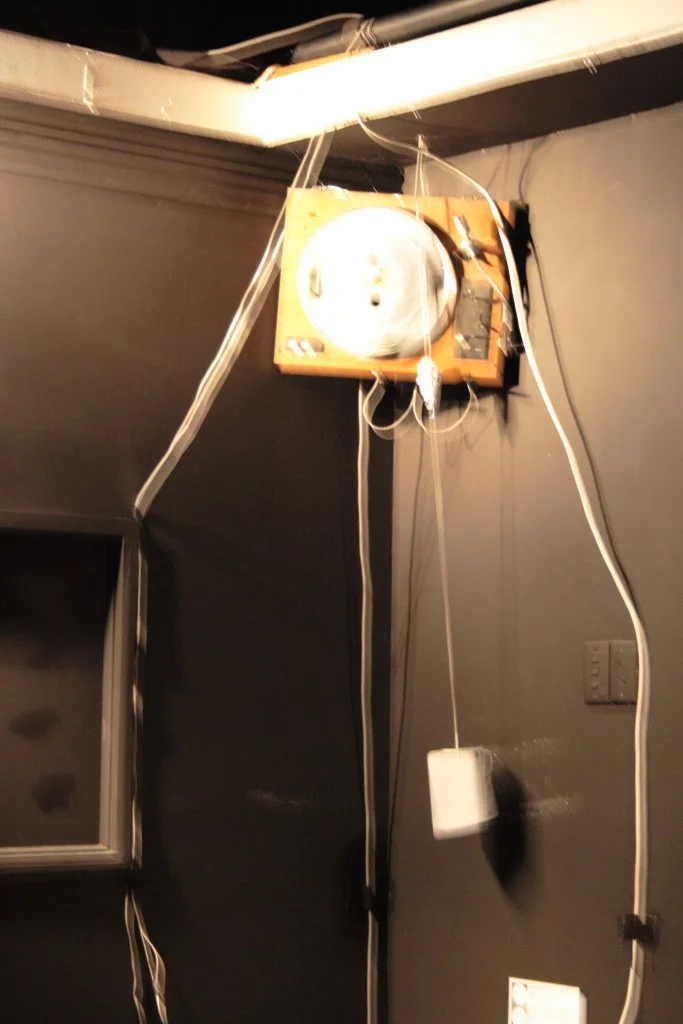

Kinetic Sound Installation (lost) Tuning forks, open circuit, 2x sound piece on 2x cd, cd players, turntable, aluminium foil, speakers, pendulum (lost)

Themes: Sound and Silence, Materiality of Sound, Chance and Accidental, Process as Form, The Poetics of Failure and Imperfection, Everyday Domesticity, Systems that Perform Themselves/Autonomous Systems, Playful Subtext

This work started with an idea about silence - or more accurately, the impossibility of silence.

There’s a well-known story about John Cage. He was supposed to have once visited an anechoic chamber - a special soundproof room designed to eliminate all echo and block out all external noise. Cage expected to experience total silence. But instead, he recounted how he heard the sound of his own body - the low pulse of his heartbeat and the high whine of his nervous system. Silence, he realised, isn’t the absence of sound. It’s just the absence of what we expect to hear. It’s also impossible in any absolute sense. There is always something.

I was captivated by that image. That in the deepest auditory void, the only thing left is the sound of a body trying to exist. A beating heart.

I was also thinking about Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room. In that piece, Lucier records himself speaking inside a room, then plays that recording back into the same room, records it again, and repeats the process. Gradually, his voice dissolves, overtaken by what have often been described as the resonant frequencies of the space itself. What’s left is the sound of the room. Its echo, its tone - the space revealing itself through repetition and degradation.

Lucier’s work is a kind of textbook example of generation loss. But it’s not just about the degradation of media- it’s about how space itself becomes part of the recording, shaping it, altering it. It was very much an influence on some of my earlier work, except in a different modality.

Both Cage and Lucier were working with the same basic truth: that sound is never neutral. It’s always shaped by the body, by the space, by the materials around it.

When I made this work, I had originally intended to record two versions of silence. One in my bedroom, and the other in an anechoic chamber. There were a few in Sydney - housed in universities - and I was a research student at the time, so with some effort, it would have been possible. But I didn’t have the energy or the mental and emotional bandwidth to follow through on the idea exactly as I’d imagined it. Life that year was very hard.

So instead, I used two recordings of silence from my bedroom, made on different days. Two different but indistinguishable failures at silence. Small, domestic, imperfect.

The physical structure of the work came together in an equally improvised way. I had no background in electronics, so the gallery director, Greg Shapley, after I explained the concept, kindly helped me wire the circuit. It was a simple open loop - one that would close whenever a metal contact brushed against another. With thanks to Greg, it felt like the perfect translation of thought into form.

The mechanism was straightforward and awkwardly poetic. A speaker hung from the ceiling and a turntable. As the turntable rotated, it set the speaker swinging - back and forth like a pendulum. The speaker swung between two metal tuning forks wired into the circuit. Each time the speaker touched one fork, the circuit closed and triggered one of the two sound recordings: one silence, then the other, then back again.

Meanwhile, the speaker, kind of heavy, unstable, slightly unpredictable - hit the corner of the gallery wall with every swing. A dull, repetitive thud that made me laugh. It reminded me - probably too literally - of a head (likely mine) banging against the wall in despair. Thud. Thud. Thud.

It’s been a long time since I made this work. Looking back, maybe more than anything, the piece was about the unintentional. The accidental.

About how the thing you try to build is never quite the thing that gets built.

About how the speaker swinging into the wall became the loudest voice in a piece about silence.

About how not making it to the anechoic chamber wasn’t a failure of completion, but became a structural part of the work.

It became a kind of machine for performing its own failure: a loop of trying, misfiring, swinging back and forth between two versions of something - of silences that are not. A system for generating its own accidents.

It was about the impossibility of silence, but also the impossibility of control - the way materials, people, gravity, and limits always push back and have minds of their own.

Like Cage’s heartbeat in the chamber, or Lucier’s voice dissolving into the walls, the real sound wasn’t the recording. It was the sound of the system itself. And the sound of trying.

The Sound of Failure Festival

Don’t Look Media Arts Gallery, Dulwich Hill, 2007

The Sound and Fury (Signifying Nothing), 2007 Kinetic Sound Installation, Installation shots

The Sound of Failure Festival, Don’t Look Media Arts Gallery, Dulwich Hill Sydney Photography: Greg Shapley & Vienna Parreno

Christina Ho on the left, me on the right, at Don’t Look Media Art Gallery, 2007 Photography: Greg Shapley

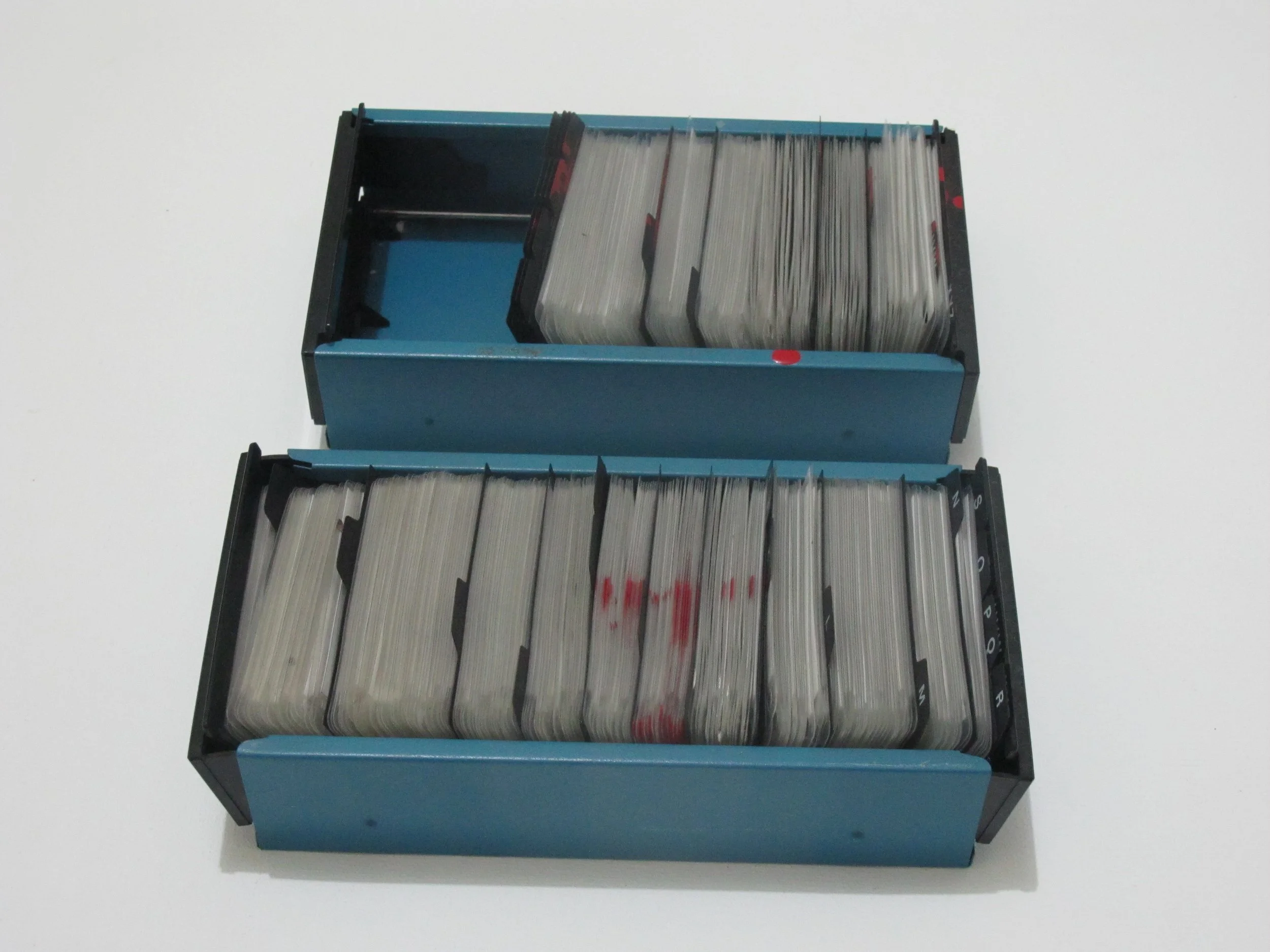

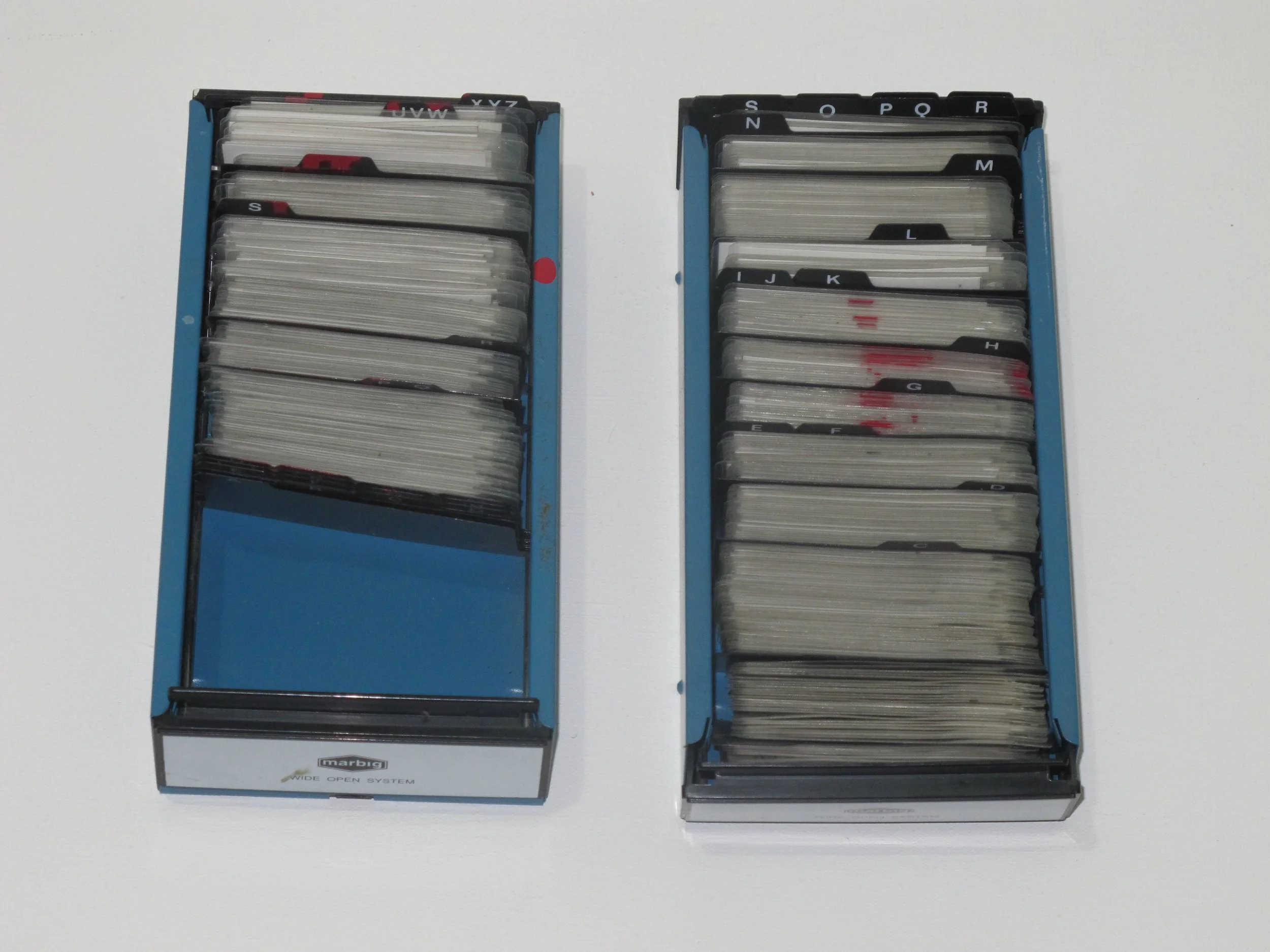

An Art Worker’s Work: From A to Z, Letter by Letter

(A Dictionary in 1,000 Cards)

Date:

c. 2003 – 2005 (lost work, surviving only in photographic documentation)

Medium:

Durational Performance/Typed transcription of The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (edition unknown), printed on standard office paper using multi–business-card-per-page format, cut to size, double-sided (term on recto, definition on verso), laminated, filed into two Marbig “Wide Open System” business card holders.

Dimensions:

Approximately 1000 cards; 2 holders each approx. 6 × 10 × 20 cm.

Lorem Ipsum

Memento Mori

(1997– 1998)

Mediums: Paintings (burned), Photographs (lost), Polaroids (mostly lost), Slides (personal archive) Location: Darlinghurst, Sydney/ Makati, Manila/ Cebu Themes: Memory, Longing, Loss, Diaspora, Recursion

NB: My archiving through the years…shall we say, has not been very systematic. The paintings were destroyed as a performance project, the prints from the performance scattered across rooms, years, cities. My mom found a box of my slides recently, so I now have those. This isn’t nostalgia. It’s poor record keeping, non-attachment, mental/psychological/logistical disarray.

I

Memento Mori - “remember you must die” - reminds us of the inevitability of death. In art, it appears through symbols like skulls, decaying objects, hourglasses, and wilting flowers : quiet reminders that life is fleeting. Their presence in the home is meant to influence how we live our daily lives. For me, the idea also took on a Stoic quality - a call to let go.

II: A Room in a Yellow House (Darlinghurst, 1997)

I made this work in my early twenties, when I didn’t yet have the language to describe what I was experiencing. Now, I’d recognise it as severely debilitating, medical-grade social anxiety. What should have been one of the best times of my life - studying art, surrounded by like-minded people - was instead marked by panic attacks and avoidance. I spent class breaks in toilets, arriving late and leaving early, dodging people by slipping into open doorways along the hallway.

I lived in the worst room of a student share house on a noisy inner-city street in Darlinghurst. There were four redeeming features: it was walking distance to my art school; it had a second kitchen we turned into a studio; it was cheap; and its exterior wall was painted a cheerful yellow. To block out the constant traffic noise, I taped cardboard over the entire wall facing the street, sealing off the only window. For the better part of a year and a half, I worked and slept in total darkness under a bare hanging lightbulb. If it weren’t so grim, it might have resembled a grunge-inspired art installation. Instead, it was simply the daily reality of being young, broke, and psychologically fragile - trying to make art, or at least be an art student, in a city full of strangers.

III: Army of Absence

One wall of the room was covered with photographs of family and friends from the Philippines. I had partly grown up there, until the age of eleven. I’d pinned the photos with Blu Tack and would show them to my housemates and their friends when they passed through my open door (I often left it ajar to let some light in), a kind of shrine to human connection - or at least the illusion of it. Like an army of absent family and friends.

I chose a few of these photographs to paint (not very well) for a class.

One was of me and my father, standing outside his family’s mausoleum in a cemetery in Manila.

Another was of me and my childhood nanny, in a sideways hug.

A third was of me with my cousins, grinning inside the Antique Room

My mother and me in the backyard of our old house in Makati, at my fourth birthday party, blindfolded, mid-swing at a terracotta piñata.

The Antique Room was one of the grand spaces we ran in and out of, named for its sole purpose: the display of antique vases and other elevated objects. The house was so vast, it felt like a world unto itself. Sometimes a whole year would pass without my crossing paths with some of the people who lived there. Like many children, I took my surroundings for granted. It hadn’t yet crystallised in my mind - at least not the way it does now - that very few children grow up with Antique Rooms, a dedicated Nursery, a private Chapel - or a forgotten, room-sized bank vault for hide-and-seek.

Each photo carried a different meaning, of course

My father and I didn’t grow up together, and the photo was one of the few I had of him as a teenager, taken when I visited the Philippines on holiday. The mausoleum - belonging to relatives I barely knew (my paternal grandparents, I think) - felt like a small monument to permanence and death in a city often marked by impermanence and precarity. Ironically, precarity had more in common with my immediate family’s new life in Australia as recent migrants than with the stability and comfort of the extended families we had left behind.

Our two nannies had been central figures in my childhood - points of warmth, care, and connection - until we migrated to Australia.

My cousins, with whom I had intermittently lived from ages seven to eleven, embodied both memories of carefree play and a complicated sadness. By then, my mother and stepfather had gone ahead of us in Australia to try their luck - “wagging” Christmas trees (a term for shaking them to fluff them up), working as a hotel porter, an assistant in a retirement village, a shoe factory - the list went on. According to my stepdad my mom cried a lot. This was the late 1980’s. We kept in touch via expensive long-distance landline calls, snail mail and care packages called Balikbayan Boxes. Meanwhile, I bounced between the home they had rented for us after we moved to Cebu (with my siblings, our nannies, twenty dogs) and our aunt’s house nearby.

I have seven cousins, spaced roughly a year apart, and I slotted in between the eldest two. There were so many of us children, and the adults had their own work and concerns, we were often left to our own devices to explore and invent our own world and forms of play. All of this, plus the formal garden and the rest of the two-hectare grounds - felt like something out of The Sound of Music. Sometimes we’d attend parties in identical dresses, cut from the same bolt of fabric.

The photograph with my mother harked back to what I imagined was a simpler moment in our lives and what I hoped had been a happy, ordinary birthday. I don’t actually remember the event, but I did have that photo. And the photo became the memory.

IV: Documentation of Documentation

Maybe painting those images was an attempt to make sense of a life too fragmented to grasp. Perhaps it was also an effort to prove - that once upon a moment, I too belonged somewhere.

Later, I burned the canvases in the backyard. A classmate photographed the destruction on slide film. A few days later, I replaced the burned canvases with Polaroids of the original paintings and re-photographed the series again. It became a documentation of documentation. A kind of meta-art, focused on absence.

If I were to translate this into video terms, it resembled generation loss crossed with a feedback loop.

I was reading Susan Sontag at the time and remembered her phrase: “A photograph is a way of stilling time’s relentless melt.”

Memento Mori. Remember you must die.

I’m not sure if I was trying to stop time - or blow it apart.

Maybe it was a work about longing. About the fragile ways we try to prove we belong - that we matter - even when we’re not sure we do.